Difference between revisions of "First Woman Professor, 1958"

| (8 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | In 1958 [[Elizabeth Wiskemann (1899-1971)]] was appointed to the Montague Burton Chair of [[International Relations]] | + | In 1958 [[Elizabeth Wiskemann (1899-1971)]] became Edinburgh University's first woman professor when she was appointed to the Montague Burton Chair of [[International Relations]]. |

== Montague Burton Chair == | == Montague Burton Chair == | ||

| Line 9: | Line 9: | ||

== Elizabeth Wiskemann == | == Elizabeth Wiskemann == | ||

| − | Elizabeth Wiskemann was the third appointee to the Chair after | + | Elizabeth Wiskemann was the third appointee to the Chair after [[James Leslie Brierly (1881–1955)|James Leslie Brierly]] (1948-1951) and [[Carlile Aylmer Macartney (1895–1978)|Carlile Aylmer Macartney]] (1951-1957). Although her name is absent from subsequent published histories, the ''University Journal'' for May 1958 certainly grasped the significance of her arrival. Announcing 'the first woman to be appointed to an Edinburgh Chair', it presented Wiskemann as 'a writer of authority on international affairs', who had held appointments as a 'press attaché to the British Legation at Berne, as a correspondent of The Economist at Rome, and as Director of the Carnegie Peace Endowment for Trieste’. |

| − | Wiskemann | + | While these are major achievements, Wiskemann's contribution to 20th-century history, in fact, ran much deeper. From 1930, Wiskemann (whose grandfather was German) worked as a political journalist in Berlin for the ''New Statesman'' and other publications, and was among the first to warn of the dangers of Nazism. So effective were her articles in alerting international readers to the true nature of Hitler’s regime that she was expelled from Germany by the Gestapo in 1937. She continued to expose Nazi plans for German expansion in her influential books ''Czechs and Germans'' (1938) and ''Undeclared War'' (1939). |

| − | + | Wiskemann did indeed spend the war as a press attaché in Switzerland, but this was cover for her true job of secretly gathering non-military intelligence from Germany and occupied Europe via the contacts she had made as a journalist in the 1930s. In May 1944, British Intelligence learned that the hitherto unknown destination to which Hungarian Jews were being deported was Auschwitz. When the allies turned down a request to bomb the railway lines (due to limited resources), Wiskemann hit on a cunning ploy. Knowing that it would be seen by Hungarian intelligence, she deliberately sent an unencrypted telegram to the Foreign Office in London. This contained the addresses of the offices and homes of the Hungarian government officials best positioned to halt the deportations and suggested that they be targeted in a bombing raid. When, quite coincidentally, several of these buildings were hit in a US raid on 2 July, the Hungarian government leapt to the conclusion that Wiskemann’s telegram had been acted upon and put an end to the deportations. Wiskemann's war-time exploits have recently been fictionalized by the Swiss author Peter Kamber in his novel ''Geheime Agentin'' (Secret Agent) (2010). | |

| − | + | == Wiskemann at Edinburgh == | |

| − | Wiskemann | + | Wiskemann continued to publish on German and Italian politics after the War. She was appointed to the Edinburgh Chair on the recommendation of William Norton Medlicott (1900-1987), Professor of International History at the London School of Economics, who described her as ‘a pleasant, active, middle-aged woman’ who would ‘be a very suitable choice’. Lectures by previous holders of the Chair had been poorly attended as they formed part of no degree course. Wiskemann, however, did much to boost the profile of her post by inviting national and international experts to lead discussion groups on issues of the day. The focus of her own teaching increasingly moved away from European issues to developments in post-colonial Africa. Click on the image, below left, to see a handwritten list of lectures and discussion groups for 1961. |

| + | <gallery widths=400px heights=400px perrow=2> | ||

| + | File:IMG 1726.JPG | ||

| + | File:IMG 1725.JPG | ||

| + | </gallery> | ||

| + | Wiskemann chose not to stand for re-election, much to the University Court’s dismay, as the Chair had proved difficult to fill. In a letter of 28 July 1960 (above right) Wickemann explained that deteriorating eyesight, exacerbated by a recent unsuccessful operation, had led to her decision. Tragically, this condition would eventually lead Wiskemann to take her own life in 1971. Wiskemann's status as Edinburgh's first woman professor is honoured by a plaque in [[George Square]]. | ||

| − | + | Six years later, Edinburgh University appointed its second female professor, and the first to be awarded a personal chair: [[Lillian Mary Pickford (1902-2002)|Mary Pickford (1902-2002)]], Professor of [[Physiology]] from 1966 to 1972. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

== Sources == | == Sources == | ||

*[[University Calendar|''Edinburgh University Calendar'']] | *[[University Calendar|''Edinburgh University Calendar'']] | ||

| + | *[[University of Edinburgh Journal|''University of Edinburgh Journal'']] | ||

[[Category:Events]][[Category:Incomplete]] | [[Category:Events]][[Category:Incomplete]] | ||

Latest revision as of 11:08, 26 March 2015

In 1958 Elizabeth Wiskemann (1899-1971) became Edinburgh University's first woman professor when she was appointed to the Montague Burton Chair of International Relations.

Montague Burton Chair

The Chair was endowed in 1948 by Sir Montague Maurice Burton (1885-1952), founder of the Burton men's clothing chain. The holder was 'bound to teach and instruct students in the principles of International Relations, particularly in connection with modern history and Public International Law'. The purpose underlying the endowment was to 'foster the study of International Relations and thus further the attainment of universal peace and the brotherhood of man based on the ideals of the United Nations Organisation'.

The holder of the Chair was to teach in the Spring term only, during which he or she was obliged to reside in Edinburgh. The appointment was for a fixed period of three years, at the end of which the holder could apply for re-election. The holder was a member of both the Faculty of Law and the Faculty of Arts.

Elizabeth Wiskemann

Elizabeth Wiskemann was the third appointee to the Chair after James Leslie Brierly (1948-1951) and Carlile Aylmer Macartney (1951-1957). Although her name is absent from subsequent published histories, the University Journal for May 1958 certainly grasped the significance of her arrival. Announcing 'the first woman to be appointed to an Edinburgh Chair', it presented Wiskemann as 'a writer of authority on international affairs', who had held appointments as a 'press attaché to the British Legation at Berne, as a correspondent of The Economist at Rome, and as Director of the Carnegie Peace Endowment for Trieste’.

While these are major achievements, Wiskemann's contribution to 20th-century history, in fact, ran much deeper. From 1930, Wiskemann (whose grandfather was German) worked as a political journalist in Berlin for the New Statesman and other publications, and was among the first to warn of the dangers of Nazism. So effective were her articles in alerting international readers to the true nature of Hitler’s regime that she was expelled from Germany by the Gestapo in 1937. She continued to expose Nazi plans for German expansion in her influential books Czechs and Germans (1938) and Undeclared War (1939).

Wiskemann did indeed spend the war as a press attaché in Switzerland, but this was cover for her true job of secretly gathering non-military intelligence from Germany and occupied Europe via the contacts she had made as a journalist in the 1930s. In May 1944, British Intelligence learned that the hitherto unknown destination to which Hungarian Jews were being deported was Auschwitz. When the allies turned down a request to bomb the railway lines (due to limited resources), Wiskemann hit on a cunning ploy. Knowing that it would be seen by Hungarian intelligence, she deliberately sent an unencrypted telegram to the Foreign Office in London. This contained the addresses of the offices and homes of the Hungarian government officials best positioned to halt the deportations and suggested that they be targeted in a bombing raid. When, quite coincidentally, several of these buildings were hit in a US raid on 2 July, the Hungarian government leapt to the conclusion that Wiskemann’s telegram had been acted upon and put an end to the deportations. Wiskemann's war-time exploits have recently been fictionalized by the Swiss author Peter Kamber in his novel Geheime Agentin (Secret Agent) (2010).

Wiskemann at Edinburgh

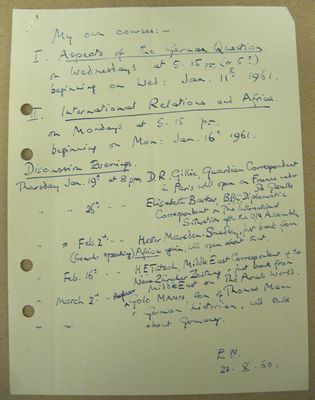

Wiskemann continued to publish on German and Italian politics after the War. She was appointed to the Edinburgh Chair on the recommendation of William Norton Medlicott (1900-1987), Professor of International History at the London School of Economics, who described her as ‘a pleasant, active, middle-aged woman’ who would ‘be a very suitable choice’. Lectures by previous holders of the Chair had been poorly attended as they formed part of no degree course. Wiskemann, however, did much to boost the profile of her post by inviting national and international experts to lead discussion groups on issues of the day. The focus of her own teaching increasingly moved away from European issues to developments in post-colonial Africa. Click on the image, below left, to see a handwritten list of lectures and discussion groups for 1961.

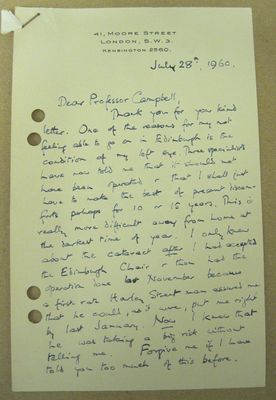

Wiskemann chose not to stand for re-election, much to the University Court’s dismay, as the Chair had proved difficult to fill. In a letter of 28 July 1960 (above right) Wickemann explained that deteriorating eyesight, exacerbated by a recent unsuccessful operation, had led to her decision. Tragically, this condition would eventually lead Wiskemann to take her own life in 1971. Wiskemann's status as Edinburgh's first woman professor is honoured by a plaque in George Square.

Six years later, Edinburgh University appointed its second female professor, and the first to be awarded a personal chair: Mary Pickford (1902-2002), Professor of Physiology from 1966 to 1972.