Difference between revisions of "Colin Maclaurin (1698-1746)"

| (17 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | '''Colin Maclaurin (1698-1746)''' was Professor of Mathematics at Edinburgh University from 1725 to 1746. | + | [[File:Macl.jpg | border | 250 px | right | thumb | Colin Maclaurin (1698-1746), engraved by Samuel Freeman after Percey (early 19th century), [[Library|Edinburgh University Library]] (Dc.2.57/3)]]'''Colin Maclaurin (1698-1746)''' was Professor of [[Mathematics]] at Edinburgh University from 1725 to 1746. |

== Early Life == | == Early Life == | ||

| − | Maclaurin was born in Kilmoden, Argyll, the third son of John MacLaurin (1658–1698), a Church of Scotland minister. After attending parish schools, he studied Classics and Mathematics at Glasgow University under Robert Simson (1687–1768). He graduated M.A. in 1713, after defending a thesis on gravity, which located its cause in Divine Will | + | Maclaurin was born in Kilmoden, Argyll, the third son of John MacLaurin (1658–1698), a Church of Scotland minister. After attending parish schools, he studied Classics and Mathematics at Glasgow University under Robert Simson (1687–1768). He graduated M.A. in 1713, after defending a thesis on gravity, which located its cause in Divine Will. Maclaurin remained at Glasgow University for a further year reading Divinity, then continued his studies independently at his uncle Daniel Maclaurin's home in Kilfinan, Argyll. In 1717, aged just nineteen, he was appointed Professor of Mathematics at Marischal College, Aberdeen University. |

| − | Maclaurin came to the attention of Isaac Newton | + | Maclaurin came to the attention of Isaac Newton (1643-1727) and his circle in London when he published two papers on the construction and mensuration of curves in 1718 and 1719. He was made a member of the Royal Society (1719) and often visited Newton. Under Newton's patronage, he published a full work on the description of curves, the hugely influential ''Geometria organica'' in 1720. In the preface, he argued that mathematics and mathematical relationships underlie nature itself. In the same year, Maclaurin published ''De linearum geometricarum proprietatibus'', in which he studied the curvature and harmonic properties of curves, and the properties of their tangents and secant lines. |

| − | In 1721 | + | In 1721, he was engaged by Lord Polworth as a tutor and travelling companion for his son. He spent three years in France, continuing his mathematical research while abroad. He won a prize-contest organized by the Académie Royale des Sciences in Paris for the best essay on the percussion of bodies, a major European triumph for Newtonian science. After his ward died in Montpellier in 1724, Maclaurin briefly resumed his duties at Aberdeen University. |

| − | + | == Maclaurin at Edinburgh University == | |

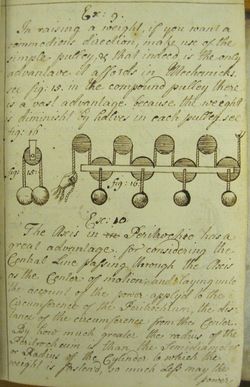

| − | + | [[File:IMG 1472.jpg | border | 250 px | right | thumb | From 'A Collection from Mr. MacLaurin's course of experiments', [[Library|Edinburgh University Library]] (Dc.7.73)]]In November 1725, Maclaurin accepted a post at Edinburgh University as joint Professor of [[Mathematics]]. He was effectively deputizing for [[James Gregory (1666-1742)]], who had held the Chair since 1692 and was now too ill to carry out his teaching duties. Gregory, however, would continue to draw a professorial salary until his death, and Maclaurin was only appointed after Isaac Newton offered to pay part of his remuneration. Maclaurin also had to pay Gregory a considerable sum for consenting to his appointment. Gregory then lived very much longer than expected, and Maclaurin was deprived of the full salary until his death in 1742. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Besides giving a three-year course from elementary to advanced mathematics, Maclaurin's classes at Edinburgh also covered experimental philosophy, surveying, fortification, geography, theory of gunnery, astronomy, and optics. His pupil [[Alexander Carlyle (1722-1805)]] recalls that: | |

| − | + | <blockquote>Mr M'Laurin was at this time a favourite professor, and no wonder, as he was the clearest and most agreeable | |

| + | lecturer on that abstract science that ever I heard. He made mathematics a fashionable study, which was felt afterwards in the war that followed in 1743, when nine-tenths of the engineers of the army were Scottish officers.</blockquote> | ||

| − | + | [[Sir Alexander Grant (1826-1884)]], Edinburgh University's most authoritative historian, describes Maclaurin as the 'life and soul' of the university, a man of 'remarkable social qualities', and a prominent figure in the capital's scientific circles. Besides his academic achievements, he was instrumental in persuading Parliament to establish a Ministers' and Professors' Widows' Fund for Scotland. | |

| − | + | == Maclaurin and the '45 == | |

| − | + | In September 1745, as Charles Edward Stuart army advanced upon Edinburgh, Maclaurin volunteered his services as a military engineer to fortify the city walls. When Edinburgh capitulated on 16 September, Maclaurin refused to submit to the Jacobite government, and fled to England, where he took refuge with Thomas Herring, Archbishop of York. He returned to Edinburgh after the Jacobites' departure in November, but caught a severe cold while travelling across snowbound countryside. His health, already undermined by his exertions in fortifying the city, never fully recovered.(See [[The University and the '45]] for more details.) | |

| − | + | Maclurin continued to dictate the last chapters of his biography of Newton on his death bed. He was tended in his final illness by [[Alexander Monro ''primus'' (1697-1767)]], the first Professor of [[Anatomy]] at Edinburgh University (1720-64) and founder of Edinburgh Medical School. At the first meeting of the [[Senatus Academicus]] after the reopening of Edinburgh University, Monro read two orations in praise of his late friend, remarking that: | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | <blockquote>acute parts and extensive learning were in Mr. M'Laurin but secondary qualities; and that he was still more nobly distinguished from the bulk of mankind by the qualities of his heart, his sincere love to God and men, his universal benevolence and unaffected piety, — together with a warmth and constancy in his friendships that was in a manner peculiar to himself</blockquote> | |

| − | + | == Research and Publications == | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

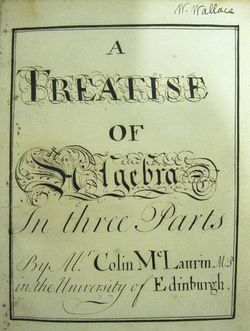

| − | + | [[File:IMG 1476.jpg | border | 250 px | right | thumb | Early MS of ''A Treatise of Algebra'' by [[Colin Maclaurin (1698-1746)]], in hand of unidentified amanuensis, [[Library|Edinburgh University Library]] (Gen.75D)]]Maclaurin wrote ''A Treatise of Algebra'' for use in his classes, which was posthumously published and became a popular textbook for the rest of century. After Newton died in 1727 Jon Conduitt (1688-1737) asked Maclaurin to collaborate in the writing of his biography. Conduitt died in 1727, but Maclaurin completed the work on his own. An Account of Sir Isaac Newton's Philosophical Discoveries, posthumously published in 1748, has long been recognized as the most authoritative statement of mainstream Newtonianism. At the same time he was working on his magnum opus, ''The Treatise of Fluxions'' (1742), which rests on his faith in Newtonian methodology. | |

| − | Colin | ||

| − | + | == Archives == | |

| − | + | *[[Lectures and Correspondence of Professor Colin Maclaurin]] | |

| − | + | == Sources == | |

| − | + | ||

| + | *[[Alexander Carlyle (1722-1805)|Alexander Carlyle]], ''Autobiography of the Rev. Dr. Alexander Carlyle, Minister of Inveresk: Containing Memorials of the Men and Events of his Time'' (Edinburgh: W. Blackwood, 1860) | ||

| + | *[[Andrew Dalzel]], ''History of the University of Edinburgh from its Foundation'', 2 vols (Edinburgh: Edmonston and Douglas, 1862) | ||

| + | *[[Sir Alexander Grant]], ''The Story of the University of Edinburgh during its First Three Hundred Years'', 2 vols (London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1884) | ||

| + | *[[John Home (1722-1808)|John Home]], ''The History of the Rebellion in the Year 1745'' (London: T. Cadell, Jun. and W. Davies, 1802) | ||

| + | *David Bayne Horn, ''A Short History of the University of Edinburgh, 1556-1889'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1967) | ||

| + | *Colin MacLaurin, ''The Collected Letters of Colin MacLaurin'', ed. Stella Mills (Nantwich: Shiva, 1982) | ||

| + | *Patrick Murdoch, 'An account of the Life and Writings of the Author', in Colin Maclaurin, ''An Account of Sir Isaac Newton's Philosophical Discoveries'' (London: A. Millar and J. Nourse, 1748) | ||

| + | *Nicholas Phillipson, 'The Making of an Enlightened University', in Robert D. Anderson, Michael Lynch, and Nicholas Phillipson, ''The University of Edinburgh: An Illustrated History'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2003), pp. 51-102. | ||

| + | *Erik Lars Sageng, 'MacLaurin, Colin (1698–1746)', ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004) [[http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/17643], accessed 12 June 2014] | ||

| + | [[Category:Academics|Maclaurin, Colin]] | ||

Latest revision as of 16:44, 4 August 2014

Colin Maclaurin (1698-1746) was Professor of Mathematics at Edinburgh University from 1725 to 1746.

Early Life

Maclaurin was born in Kilmoden, Argyll, the third son of John MacLaurin (1658–1698), a Church of Scotland minister. After attending parish schools, he studied Classics and Mathematics at Glasgow University under Robert Simson (1687–1768). He graduated M.A. in 1713, after defending a thesis on gravity, which located its cause in Divine Will. Maclaurin remained at Glasgow University for a further year reading Divinity, then continued his studies independently at his uncle Daniel Maclaurin's home in Kilfinan, Argyll. In 1717, aged just nineteen, he was appointed Professor of Mathematics at Marischal College, Aberdeen University.

Maclaurin came to the attention of Isaac Newton (1643-1727) and his circle in London when he published two papers on the construction and mensuration of curves in 1718 and 1719. He was made a member of the Royal Society (1719) and often visited Newton. Under Newton's patronage, he published a full work on the description of curves, the hugely influential Geometria organica in 1720. In the preface, he argued that mathematics and mathematical relationships underlie nature itself. In the same year, Maclaurin published De linearum geometricarum proprietatibus, in which he studied the curvature and harmonic properties of curves, and the properties of their tangents and secant lines.

In 1721, he was engaged by Lord Polworth as a tutor and travelling companion for his son. He spent three years in France, continuing his mathematical research while abroad. He won a prize-contest organized by the Académie Royale des Sciences in Paris for the best essay on the percussion of bodies, a major European triumph for Newtonian science. After his ward died in Montpellier in 1724, Maclaurin briefly resumed his duties at Aberdeen University.

Maclaurin at Edinburgh University

In November 1725, Maclaurin accepted a post at Edinburgh University as joint Professor of Mathematics. He was effectively deputizing for James Gregory (1666-1742), who had held the Chair since 1692 and was now too ill to carry out his teaching duties. Gregory, however, would continue to draw a professorial salary until his death, and Maclaurin was only appointed after Isaac Newton offered to pay part of his remuneration. Maclaurin also had to pay Gregory a considerable sum for consenting to his appointment. Gregory then lived very much longer than expected, and Maclaurin was deprived of the full salary until his death in 1742.

Besides giving a three-year course from elementary to advanced mathematics, Maclaurin's classes at Edinburgh also covered experimental philosophy, surveying, fortification, geography, theory of gunnery, astronomy, and optics. His pupil Alexander Carlyle (1722-1805) recalls that:

Mr M'Laurin was at this time a favourite professor, and no wonder, as he was the clearest and most agreeable lecturer on that abstract science that ever I heard. He made mathematics a fashionable study, which was felt afterwards in the war that followed in 1743, when nine-tenths of the engineers of the army were Scottish officers.

Sir Alexander Grant (1826-1884), Edinburgh University's most authoritative historian, describes Maclaurin as the 'life and soul' of the university, a man of 'remarkable social qualities', and a prominent figure in the capital's scientific circles. Besides his academic achievements, he was instrumental in persuading Parliament to establish a Ministers' and Professors' Widows' Fund for Scotland.

Maclaurin and the '45

In September 1745, as Charles Edward Stuart army advanced upon Edinburgh, Maclaurin volunteered his services as a military engineer to fortify the city walls. When Edinburgh capitulated on 16 September, Maclaurin refused to submit to the Jacobite government, and fled to England, where he took refuge with Thomas Herring, Archbishop of York. He returned to Edinburgh after the Jacobites' departure in November, but caught a severe cold while travelling across snowbound countryside. His health, already undermined by his exertions in fortifying the city, never fully recovered.(See The University and the '45 for more details.)

Maclurin continued to dictate the last chapters of his biography of Newton on his death bed. He was tended in his final illness by Alexander Monro ''primus'' (1697-1767), the first Professor of Anatomy at Edinburgh University (1720-64) and founder of Edinburgh Medical School. At the first meeting of the Senatus Academicus after the reopening of Edinburgh University, Monro read two orations in praise of his late friend, remarking that:

acute parts and extensive learning were in Mr. M'Laurin but secondary qualities; and that he was still more nobly distinguished from the bulk of mankind by the qualities of his heart, his sincere love to God and men, his universal benevolence and unaffected piety, — together with a warmth and constancy in his friendships that was in a manner peculiar to himself

Research and Publications

Maclaurin wrote A Treatise of Algebra for use in his classes, which was posthumously published and became a popular textbook for the rest of century. After Newton died in 1727 Jon Conduitt (1688-1737) asked Maclaurin to collaborate in the writing of his biography. Conduitt died in 1727, but Maclaurin completed the work on his own. An Account of Sir Isaac Newton's Philosophical Discoveries, posthumously published in 1748, has long been recognized as the most authoritative statement of mainstream Newtonianism. At the same time he was working on his magnum opus, The Treatise of Fluxions (1742), which rests on his faith in Newtonian methodology.

Archives

Sources

- Alexander Carlyle, Autobiography of the Rev. Dr. Alexander Carlyle, Minister of Inveresk: Containing Memorials of the Men and Events of his Time (Edinburgh: W. Blackwood, 1860)

- Andrew Dalzel, History of the University of Edinburgh from its Foundation, 2 vols (Edinburgh: Edmonston and Douglas, 1862)

- Sir Alexander Grant, The Story of the University of Edinburgh during its First Three Hundred Years, 2 vols (London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1884)

- John Home, The History of the Rebellion in the Year 1745 (London: T. Cadell, Jun. and W. Davies, 1802)

- David Bayne Horn, A Short History of the University of Edinburgh, 1556-1889 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1967)

- Colin MacLaurin, The Collected Letters of Colin MacLaurin, ed. Stella Mills (Nantwich: Shiva, 1982)

- Patrick Murdoch, 'An account of the Life and Writings of the Author', in Colin Maclaurin, An Account of Sir Isaac Newton's Philosophical Discoveries (London: A. Millar and J. Nourse, 1748)

- Nicholas Phillipson, 'The Making of an Enlightened University', in Robert D. Anderson, Michael Lynch, and Nicholas Phillipson, The University of Edinburgh: An Illustrated History (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2003), pp. 51-102.

- Erik Lars Sageng, 'MacLaurin, Colin (1698–1746)', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004) [[1], accessed 12 June 2014]