Difference between revisions of "William Cleghorn (1718-1754)"

| (18 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

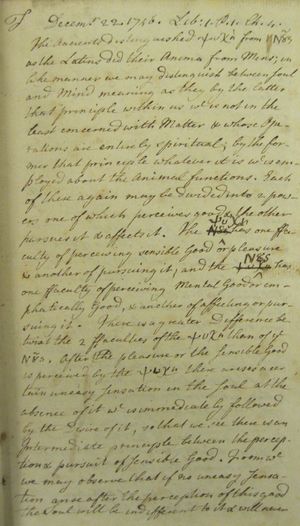

| − | + | [[File:IMG 1474.JPG | border | 300 px | right | thumb | Students notes of lectures in Moral Philosophy by William Cleghorn (1718-1754), taken down 1746-1747, [[Library|Edinburgh University Library]] (Dc.3.3-6)]]'''William Cleghorn (1718-1754)''' was Professor of [[Moral Philosophy]] at Edinburgh University from 1745 to 1754. | |

| − | + | == Early life == | |

| − | + | Relatively little is known of the early life of William Cleghorn. The son of a brewer and burgess of Edinburgh, he graduated MA from Edinburgh University in 1739. He must also have attended Divinity classes, for he was licensed to preach but never held a church appointment. In 1739-1740, Cleghorn was employed as a private tutor to Sir Henry Nisbet of Dean, but returned to Edinburgh University in 1742 as a deputy for [[Sir John Pringle (1707-1782)]], Professor of Moral Philosophy. | |

| − | Cleghorn | + | == Cleghorn and Edinburgh University == |

| − | Cleghorn and Edinburgh | + | Pringle was absent on war service, working as a military surgeon to the British Army who were then engaged in Flanders (as part of the War of Austrian Succession). Cleghorn was one of several deputies appointed by the [[Senatus Academicus]] to conduct Pringle's classes before he was finally induced to resign the chair in 1745. The [[Town Council]] was keen to raise the standing of the vacant post and initially offered it to Francis Hutcheson (1694-1746), Professor of Moral Philosophy at Glasgow University and founder of the Scottish school of philosophy. Hutcheson declined, and [[David Hume (1711-1776)]], now widely regarded as Scotland's greatest philosopher, applied in his place. His candidature was controversially blocked by the clergy of Edinburgh who suspected Hume of being both an atheist and sympathetic to Jacobitism. Cleghorn,a committed Whig and staunch Presbyterian, proved a more acceptable choice. |

| − | + | Cleghorn was appointed on 5 June 1745 and soon had the opportunity to demonstrate his political and religious zeal. As Charles Edward Stuart's Jacobite army approached Edinburgh in September 1745, a College Company of Volunteers was formed to help defend the city. Along with his friends [[William Robertson (1721-1793)]] (future [[Principal]] of the University), [[Alexander Carlyle (1722-1805)]], and [[John Home (1722-1808)]], Cleghorn was one of its most ardent members. When it became apparent that Edinburgh would capitulate, he urged the volunteers to join the British army which had landed at Dunbar. With Carlyle and Robertson, he made his way to Dunbar to offer his services to General Sir John Cope. The student volunteers were employed as scouts in the build-up to the Battle of Prestonpans (21 September 1745), which ended in an ignominious defeat for the government forces. Cleghorn was also a member of the Revolution Club, dedicated to protecting the Protestant and anti-Absolutist principles of 'Glorious Revolution' of 1688. See [[The University and the '45]] for more details. | |

| − | Cleghorn | + | == Cleghorn's Philosophy == |

| − | Cleghorn held the | + | Cleghorn held the Chair of Moral Philosophy for the rest of his life. He published no philosophical works, but student lecture notes held by Edinburgh University Library suggest that his thought was essentially Ciceronian. The notes also reveal a passionate opposition to absolutism and despotism, and a possible leaning towards republicanism. Although not a major figure, Cleghorn has perhaps been unfairly belittled by commentators who have ridiculed his credentials for the chair when compared to Hume. As significant a thinker as [[Adam Ferguson (1723-1816)]] acknowledged Cleghorn's influence. Cleghorn's early death at the age of thirty-six may also have prevented him from making a major written contribution to moral philosophy. |

| − | + | == Archives == | |

| − | Professor William Cleghorn | + | *[[Lectures of Professor William Cleghorn]] |

| − | [[Category:Academics|Cleghorn, William]] | + | == Links == |

| + | *[[David Hume's Failed Application for Chair of Moral Philosophy, 1745]] | ||

| + | *[[The University and the '45]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | == Sources == | ||

| + | |||

| + | *[[Alexander Carlyle (1722-1805)|Alexander Carlyle]], ''Autobiography of the Rev. Dr. Alexander Carlyle, Minister of Inveresk: Containing Memorials of the Men and Events of his Time'' (Edinburgh: W. Blackwood, 1860) | ||

| + | *[[Andrew Dalzel]], ''History of the University of Edinburgh from its Foundation'', 2 vols (Edinburgh: Edmonston and Douglas, 1862) | ||

| + | *Alexander Du Toit, 'Cleghorn, William (1718–1754)', ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004)[[http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/63629], accessed 23 June 2014] | ||

| + | *[[Sir Alexander Grant]], ''The Story of the University of Edinburgh during its First Three Hundred Years'', 2 vols (London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1884) | ||

| + | *[[John Home (1722-1808)|John Home]], ''The History of the Rebellion in the Year 1745'' (London: T. Cadell, Jun. and W. Davies, 1802) | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Category:Academics|Cleghorn, William]][[Category:Alumni|Cleghorn, William]] | ||

Latest revision as of 13:57, 17 February 2015

William Cleghorn (1718-1754) was Professor of Moral Philosophy at Edinburgh University from 1745 to 1754.

Early life

Relatively little is known of the early life of William Cleghorn. The son of a brewer and burgess of Edinburgh, he graduated MA from Edinburgh University in 1739. He must also have attended Divinity classes, for he was licensed to preach but never held a church appointment. In 1739-1740, Cleghorn was employed as a private tutor to Sir Henry Nisbet of Dean, but returned to Edinburgh University in 1742 as a deputy for Sir John Pringle (1707-1782), Professor of Moral Philosophy.

Cleghorn and Edinburgh University

Pringle was absent on war service, working as a military surgeon to the British Army who were then engaged in Flanders (as part of the War of Austrian Succession). Cleghorn was one of several deputies appointed by the Senatus Academicus to conduct Pringle's classes before he was finally induced to resign the chair in 1745. The Town Council was keen to raise the standing of the vacant post and initially offered it to Francis Hutcheson (1694-1746), Professor of Moral Philosophy at Glasgow University and founder of the Scottish school of philosophy. Hutcheson declined, and David Hume (1711-1776), now widely regarded as Scotland's greatest philosopher, applied in his place. His candidature was controversially blocked by the clergy of Edinburgh who suspected Hume of being both an atheist and sympathetic to Jacobitism. Cleghorn,a committed Whig and staunch Presbyterian, proved a more acceptable choice.

Cleghorn was appointed on 5 June 1745 and soon had the opportunity to demonstrate his political and religious zeal. As Charles Edward Stuart's Jacobite army approached Edinburgh in September 1745, a College Company of Volunteers was formed to help defend the city. Along with his friends William Robertson (1721-1793) (future Principal of the University), Alexander Carlyle (1722-1805), and John Home (1722-1808), Cleghorn was one of its most ardent members. When it became apparent that Edinburgh would capitulate, he urged the volunteers to join the British army which had landed at Dunbar. With Carlyle and Robertson, he made his way to Dunbar to offer his services to General Sir John Cope. The student volunteers were employed as scouts in the build-up to the Battle of Prestonpans (21 September 1745), which ended in an ignominious defeat for the government forces. Cleghorn was also a member of the Revolution Club, dedicated to protecting the Protestant and anti-Absolutist principles of 'Glorious Revolution' of 1688. See The University and the '45 for more details.

Cleghorn's Philosophy

Cleghorn held the Chair of Moral Philosophy for the rest of his life. He published no philosophical works, but student lecture notes held by Edinburgh University Library suggest that his thought was essentially Ciceronian. The notes also reveal a passionate opposition to absolutism and despotism, and a possible leaning towards republicanism. Although not a major figure, Cleghorn has perhaps been unfairly belittled by commentators who have ridiculed his credentials for the chair when compared to Hume. As significant a thinker as Adam Ferguson (1723-1816) acknowledged Cleghorn's influence. Cleghorn's early death at the age of thirty-six may also have prevented him from making a major written contribution to moral philosophy.

Archives

Links

Sources

- Alexander Carlyle, Autobiography of the Rev. Dr. Alexander Carlyle, Minister of Inveresk: Containing Memorials of the Men and Events of his Time (Edinburgh: W. Blackwood, 1860)

- Andrew Dalzel, History of the University of Edinburgh from its Foundation, 2 vols (Edinburgh: Edmonston and Douglas, 1862)

- Alexander Du Toit, 'Cleghorn, William (1718–1754)', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004)[[1], accessed 23 June 2014]

- Sir Alexander Grant, The Story of the University of Edinburgh during its First Three Hundred Years, 2 vols (London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1884)

- John Home, The History of the Rebellion in the Year 1745 (London: T. Cadell, Jun. and W. Davies, 1802)